Feature: Afghan refugees who are reluctant to return

Feature: Afghan refugees who are reluctant to return

CHAGAI CAMP, Pakistan (UNHCR) - This year, the Afghan refugees of Chagai camp started construction of the largest mosque built since the first residents arrived in the wake of the 1979 Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.

For anyone who expects all Afghans will go home under the voluntary repatriation programme operated by the UN refugee agency, this is clear evidence that many refugees are likely to be still in Pakistan when the assistance winds down in 2005 as envisaged under the current agreement with Pakistan.

"We have yet to consult our people on the question of returning," said Sardar Haji Murad Khan at a meeting of Afghan elders in Chagai camp. "We are waiting for things to get clearer and then we will decide. Otherwise we are quite comfortable in Pakistan."

Chagai camp is one of four refugee settlements in the remote Dalbandin area, a thinly-populated region of bare sand and blackened rock south of Afghanistan in the part of Pakistan that extends to meet Iran.

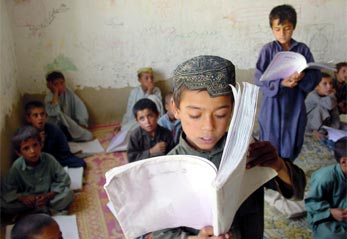

The camps, which also include Lejay Karez, Posti and Girdi Jungle, hold nearly 66,000 refugees. Unlike some camps in Pakistan that draw outside visitors, these refugees are seen by few outside of the UNHCR field office in the town of Dalbandin and the agency's implementing partners providing health and educational support.

In winter, a bitter wind whips across the desert sands, which merge into the Dasht al Margo - the Desert of Death - of southern Afghanistan. In summer, the temperatures at the UNHCR office reached 54° Celsius this year.

Just as the terrain of Pakistan and Afghanistan is almost indistinguishable, so is the population. In Chagai camp, the 13,678 refugees have reportedly been joined by thousands of people with Pakistani citizenship. Girdi Jungle, with 34,000 refugees, is the largest community in the region.

Three of the refugee camps lie along a newly paved road to the administrative centre of Dalbandin. The road curves through the desert near the edge of Pakistani territory, but only a dirt track leads off past a Frontier Constabulary post toward the unmarked Afghan border.

Most of the refugees, many in Pakistan for almost a quarter century, come from the nearby provinces of Afghanistan, especially Helmand where one of Afghanistan's few rivers makes agriculture possible.

Some do express interest in returning. One elder said he represented 150 families who want assistance to return over the nearby border to Afghanistan, instead of going via the distant UNHCR verification office in Quetta.

Arranging a crossing of the normally closed border would not be difficult, but there are questions about ownership of the land they want to return to in Helmand, one of the property disputes that are among the most intractable problems in Afghanistan.

Other tentative requests by refugees to repatriate under the Facilitated Group Return programme - in which UNHCR agency staff in Afghanistan help prepare the receiving locations - are complicated by various doubts about whether they can actually go to their former homes.

From elsewhere in Pakistan, more than 315,000 refugees have returned to Afghanistan this year, following a repatriation of more than 1.5 million in 2002. That leaves about 1.1 million refugees still in camps and an unknown, but substantial number, in urban areas of Pakistan.

But, with continuing security problems in southern Afghanistan and only one year of good rain after years of drought, most refugees around Dalbandin appear to have little interest in returning before UNHCR's three-year voluntary repatriation programme ends.

Under the agreement signed by Afghanistan, Pakistan and UNHCR, the UN refugee agency is willing to screen remaining Afghans to see who needs the protection of official refugee status. What happens to the rest will be the subject of debate over the next two years.

"My appeal would be, 'don't just forget us after 2005,' because the problem would still be alive, and we will have a huge burden on our economy," Aftab Ahmed Khan Sherpao, Pakistan's minister responsible for refugees, told the annual meeting of UNHCR's Executive Committee in Geneva last week.

In Leejay Karez camp, the leader of the 4,841-strong community, Haji Aurang Noorzai, expressed doubts about most aspects of Afghanistan's recovery from 25 years of war.

In contrast, he said in his carpet-lined meeting room, his people enjoy both security and employment by living on the Pakistani side of the border. The refugees have even built their own water system.

"Return to Afghanistan by 2005?" responded the village elder when asked if his people would repatriate. "We will not return there even in the next 2,000 years if we are not sure that in Afghanistan the lives and dignity of people are safe."

He added, "In the camp we have secure shelter to which our people return after doing their work. What guarantee do we have in Afghanistan?"

By Jack Redden

UNHCR Pakistan